David Kim, a senior majoring in computer science at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, has applied to 326 jobs so far, but only got an interview for three of them.

Kim said this is normal for computer science majors like her who are still job hunting despite graduation approaching, with some of her classmates saying they’ve applied to around 1,000 jobs and are still waiting to hear back.

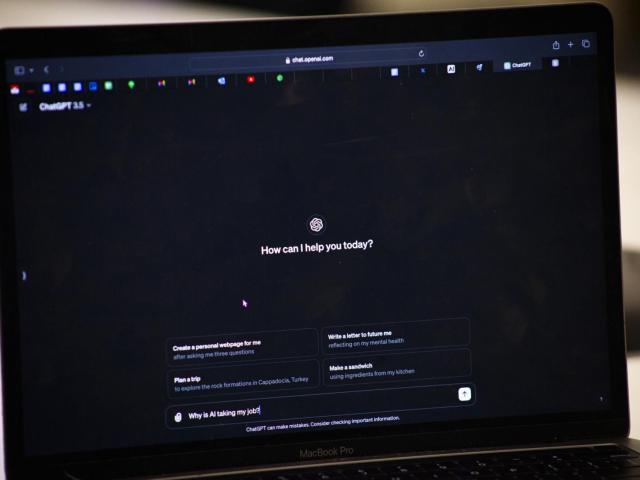

Kim said career competitiveness is often driven by the economy and the job market, but also by a new wave of technology: artificial intelligence.

AI aims to be as intelligent as or better than humans at solving problems, and such advanced technology is economically attractive to companies, Kim said.

“Let’s see what happens. [companies] “We’re going to eliminate jobs through automation,” he said. “From an economic standpoint, [AI] “There will definitely be job losses. That’s a scary thing.”

Mohammad Hossein Jarrahi, a professor at the University of North Carolina at Colorado School of Information and Library Science who studies the relationship between humans and AI in the workplace, believes the threat of AI boils down to one concept: self-learning.

“[AI systems] “They’re adaptive in their learning, and that’s both a source of opportunity and a source of threat,” Jarrahi said. “If they’re learning really well, what happens to me? If they’re learning independently of me, the knowledge worker, what is my contribution?”

Jarrahi said that while blue-collar jobs are typically at risk from new technology and automation, this new wave of AI will also impact degree-seeking knowledge workers who were previously thought to be unaffected.

“If you’re not worried, you’re probably not paying attention,” Jarrahi said.

Kim said that while it’s hard to predict the future, he knows that companies will have to find ways to compete in an evolving job market influenced by AI.

“For the industry, [AI] “Actually, that’s a good thing. But for graduating seniors, or juniors, or sophomores who are currently studying computer science, or high school graduating students who want to study computer science, it’s a pretty big concern,” Kim said. “I don’t know what’s going to happen. I don’t think anybody knows. But, as always, we’re going to have to adapt in some way.”

Undergraduate student concerns

Fears of AI taking over jobs aren’t just affecting computer science students.

Sarayu Thondapu, a sophomore at UNC-CH, has already had many conversations about how AI will impact her future.

Thondup, currently a pre-law student studying economics and political science, was visiting his parents in Charlotte, North Carolina, over winter break when his uncle warned him about the potential impact of AI on the legal industry. For example, the AI program LegalGPT can perform similar tasks as a legal assistant or paralegal.

Scott Geyer, a professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Hussman School of Media and Journalism, said junior lawyers risk losing their jobs as AI becomes able to do the same tasks, such as reviewing documents and writing briefs.

“Analyzing information and doing it quickly and efficiently is something that AI can already do better, so it’s going to get better, faster and cheaper,” Geier says. “And once there’s something better, faster and cheaper, a robot will do it.”

Now, the AI is making Thondup question his career.

“I wanted to go into law to be someone who could help people, someone who could really empathize with the cases I was working on and be of service to them. I’m not going to leave them alone,” Thondup said. “I guess I’m worried that if I rely too much on ChatGPT and artificial intelligence, I’ll forget why I’m there in the first place.”

As Thondap neared the middle of his undergraduate career, he began to think about his future graduation and often wondered whether it was all worth it.

“We spent four years of our lives in undergrad. We studied hard. We did a lot to get to where we are now and we gained a lot of experience,” Thondup said. “But I think it’s really frightening to realize that what we were so responsible for building might end up making all our efforts go to waste.”

She said that because she has a “survival mentality,” she is now incorporating tech classes and data science certification into her studies to make herself more competitive in the job market and secure her future.

“I think this is something we all accept, that you basically need to know something about computers to survive in this world,” Thondup said.

But she worries that too much focus on computers will cause this generation to forget how to communicate with passion and humanity, so Thondup minored in creative writing to compete with AI.

Kim also considered changing his graduation plans: He had initially focused on applying for software engineering and web development jobs, but with the rise of AI, he became interested in applying for machine learning roles.

But those roles often require additional education, time and money, so they should still be considered, he said.

AI vs. College Degrees

The value of a college degree has always been debated, Jarrahi said, but the value of higher education in the age of AI brings new twists to the debate.

Google offers a program that allows anyone interested in technology to earn a career certification without any prior experience, and the company touts the program on its website as a viable path to landing an in-demand job within six months.

It’s cheaper and less time-consuming than college, and Google says the program is equivalent to a four-year degree, Geyer said.

“College tuition is too expensive. It’s not worth the price tag,” Geyer said. “And people are realizing that if AI is now part of the equation, that mindset is only going to accelerate.”

Duke University currently offers a degree program for studying AI, the Duke AI Engineering Masters program.

Jared Bailey is the current president of the AI Competition Club and a master’s student at Duke University, where tuition typically costs $75,877 for 12 months (two semesters and a summer course).

The program also includes flexible education options, including a 16-month extended course costing up to $95,000 and a 24-month online program costing $98,970.

But Bailey believes the program is worthwhile.

“Smart students will examine their education to see if it will provide a return on their investment,” he says. “I can’t imagine a world in which students can’t find a field that will provide a return.”

Duke’s AI program website says the degree promises “excellent graduate outcomes” in engineering and data science jobs.

Bailey said AI could be useful in other industries as well as science, engineering and technology: One of his classmates in the program is a doctor who uses computer vision to identify diseases in high-resolution photos, he said.

Bailey compared advances in AI to the invention of the camera, the internet and the personal computer, saying that while they initially faced resistance, they ultimately ended up improving human activities.

“Duke is very open to students using AI,” Bailey said. “When I was younger, educators resisted students using calculators and the internet. It’s refreshing to see Duke take a different stance and embrace this new technology.”

AI is there to enhance our jobs, not compete with them, he said.

Use of AI

Professional editor Erin Servais believes humans can collaborate with AI and has incorporated this into her career.

Servais has been editing professionally since 2008, from line editing to development editing. Last year, his first experience using ChatGPT for copy editing changed his career.

“I was amazed at how accurate it was and how fast it was,” Servais said, “and I knew this was going to have a huge impact on our profession. I knew that right away the first time I tried it.”

She then created an “AI for Editors” course to educate editors on how AI programs like ChatGPT are changing the editing profession.

Because, she said, AI will eventually replace editors.

“People are losing their jobs to artificial intelligence, and in a totally unintelligent way,” Servais said. “It’s not a good thing, it’s not helping readers, it’s not helping writers, it’s not helping anybody.”

But if editors learn to use AI, editing can become more accurate and efficient for their organizations, she said, and editors with AI knowledge could find their jobs more stable and valuable in the workplace.

Servais said the next evolution of the job will revolve around guiding AI programs and reviewing their behavior, rather than manually making changes to documents, but the human element will still be essential, she said.

“We don’t want to outsource the work to AI because we need to double-check that what it produces is high quality and fact-based, and for that we still need humans,” Servais said.

Geyer said AI could take over the heavy lifting in most specialties, but human oversight would still be needed, though he said this would happen gradually.

He believes that students graduating today won’t lose their jobs to AI if they’re prepared, but those who don’t learn about it will be left behind, he said.

Geyer said students need to gain an “edge” by working with AI in ways that others can’t, and that’s exactly what universities need to teach.

“You have to make yourself relevant by using AI in the work you do,” Geyer says. “What’s going to happen is that after you leave here, employers will ask, ‘Can a stranger walking by come in and do the same job?’ [a student] “What are you doing just writing prompts to an AI? If the answer is yes, you’re out of a job.”